Kicking the Pigeon # 6 - “Bridgeport”

Officers Seinitz, Savickas, Stegmiller, Utreras, and Schoeff were, until recently, familiar presences at Stateway Gardens and other South Side public housing developments. With the exception of Seinitz who is known as "Macintosh," they are referred to on the street not by their names but as "the skullcap crew" (they often wear watch caps) or "the skinhead crew" (several have buzz cuts). They are reputed to prey on the drug trade--routinely extorting money, drugs, and guns from drug dealers--in the guise of combating it. But what distinguishes them, above all, say residents, is their racism. Several are rumored to have swastika tattoos on their bodies. One resident described them to me as "KKK under blue-and-white." And black officers have been heard to refer to them as "that Aryan crew." "They get their jollies humiliating black folks," a former Stateway resident told me. "They get off on it."

Diane Bond, in the aftermath of her encounters with the crew, seemed stunned by the ferocity of their racism. “Me, I don’t see no color, but they’re prejudiced,” she observed. “I hear they’re from Bridgeport.”

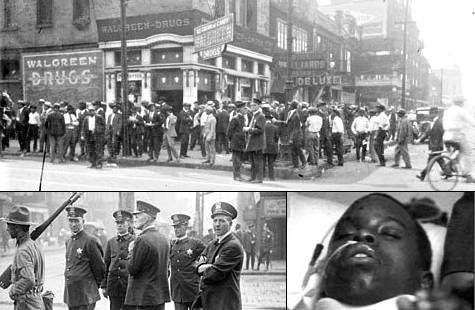

The officers were in fact assigned at the time to the Public Housing South unit of the Chicago Police Department. Until it was disbanded in the fall of 2004, Public Housing South operated out of offices at 38th and Cottage Grove in the Ida B. Wells development. The rumor that they were “from Bridgeport” was telling. For Stateway residents, “Bridgeport” carries a heavy freight of meanings and associations. It refers to the traditional seat of political power in the city. It evokes an intimate landscape containing great distances: Bridgeport is just across the Dan Ryan Expressway but a world away. And it recalls a bitter history of racial violence that includes among its defining events the 1919 riots when 4,000 blacks massed at 35th and State to defend their neighborhood against marauding white gangs, and the cruel 1997 beating that left Lenard Clark, a 13-year-old Stateway boy who had ventured into Bridgeport on his bicycle, brain damaged.

There is knowledge on the street about the skullcap crew; it resides in people's nerve endings; it flows readily between those who share a body of experience and a common language. The Bridgeport rumor reflects an effort to make sense of that knowledge by constructing a context around it. It's an effort to place the crew. Such attempts at explanation can give rise to rumors and, at least in the case of "Macintosh," to urban myths. (Last year when he was not seen at Stateway for several weeks, competing rumors circulated to explain his absence: he had been arrested in a federal sting operation; he had left the police force to become a bounty hunter; and he had gone to Iraq to fight as a mercenary.) Yet the challenge presented by the knowledge of the street remains.

As a reporter, I confront a similar challenge: to place the skullcap crew within broader contexts that help explain what at first seems inexplicable. Assume for the moment that Diane Bond's account is true. What possible rationale could there be for members of the skullcap crew to repeatedly invade her home and her body? These incidents have come to public attention because of the circumstance--highly unusual in the setting of public housing--that Bond has relationships that enabled her to get skilled lawyers to take her case. It should not be assumed because the incidents have come to light that they are the worst crimes the crew committed during the years they worked in South Side public housing communities. They may not even be the worst crimes they committed on the dates in question.

Against this background and making these assumptions, we will explore the multiple contexts that frame the Diane Bond story. Those contexts include "the war on drugs" as waged in Chicago public housing, the CHA's Plan for Transformation, and the policies and practices of the CPD with respect to complaints of police misconduct. At the center of this narrative inquiry is the question: if a group of rogue police officers operated for years in Chicago public housing with impunity, what conditions would be required to make possible their criminal careers?

Kicking the Pigeon # 5 - April 30, 2003

On April 30, 2003—two days after her second encounter with the police—Bond and her boyfriend Billie Johnson went downstairs at about 11:30 p.m. They were going to the store to get some wine. As they came out of the stairwell into the elevator corridor in the lobby, they encountered Officers Stegmiller and Savickas. Stegmiller grabbed Bond by the arm.

“Where are you going?” he demanded.

“To the store.”

She had her keys in her hand.

“Give me your keys,” he said. “Give me your goddamn keys.”

“I’m not going to give you my keys,” she protested. “I’m not going through that again.”

She shifted her keys from one hand to the other and put them in her pocket. Stegmiller grabbed her around the throat and pushed her up against the elevator door.

“I’ll beat your motherfucking ass.”

“Somebody please help me,” she called out. “Please help me.”

Savickas stood by, while Stegmiller choked Bond. When Johnson appealed to him to intervene, Savickas gave him a hard push in the chest.

Only when other residents came on the scene did Stegmiller release Bond and tell her, “Get the fuck out of here.”

“I was crying, I was angry. I was hysterical,” Bond recalled. “I told my old man, ‘I’m so tired. I’m tired of this.’”

She and Johnson went directly to the Office of Professional Standards in the IIT building at 35th and State. Although OPS is open 24 hours a day, security personnel in the lobby of the building would not let her go up to the office. She left and went to the administrative headquarters of the Chicago Police Department at 35th and Michigan. The officers at the desk were not welcoming. They threatened to put Bond and Johnson in lockup. In the end, they took down her name and address. She then went to a store on the corner of 37th and State and attempted to call OPS, but the phone in the store was dead.

It was raining hard. Bond and Johnson returned to the building. The police were still there. They slipped in. He went to her apartment on the eighth floor. She went upstairs to thank the neighbors whose presence had stopped Stegmiller’s assault on her. In a vacant apartment on the fifteenth floor, she saw Seinitz—“Macintosh.” He didn’t see her. She fled the building. Again, she attempted to go to OPS, and again she was barred by security. She returned to 3651-53 South Federal and waited outside in the rain and darkness for about half an hour until the police left the building. Then she climbed the stairs to her home.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, May 1, 2003, and continuing to the present; an interview with Billie Johnson; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officers Robert Stegmiller and Christ Savickas deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

Kicking the Pigeon # 4 - Old Wounds

Being forced to expose herself while Officer Seinitz and the others threatened her was “like a dry rape,” Diane Bond told me the day after the April 28 incident. She mentioned then that she had suffered violence at the hands of men when she was a girl. Later she told me the full story.

It has been my fate as a man and as a journalist to hear many such stories. Inevitably, I feel a tension between my hunger for the details—details that may obscure more than they reveal—and the desire to cover my ears. I resist entering imaginatively into the experience of being rendered utterly powerless. Although I am acutely aware of this dynamic, I still must work to resist seizing on details that explain why the victim was raped. My impulse is not so much to blame the victim as it is to find a way to differentiate myself and those close to me from the suffering person before me.

As Diane Bond began to tell her story, I saw a familiar upwelling in her eyes—not tears but rather a sudden shift in emotional gravity.

She grew up on the West Side. Her natural father left when she was a small child. Her mother remarried. Diane was six years old at the time. From the start, her stepfather abused her. As a little girl, she had long hair. He would take her into the bathroom, ostensibly to comb her hair, sit her up on the washbasin, and fondle her. He told her that if she ever said anything, her mother would go to jail and she would never see her again.

Silenced by his threats, she didn’t say anything, until one day her mother caught her and her brother pretending to smoke cigarette butts they had fished out of an ashtray.

“I’ll have your stepfather whup you,” she told the children.

“No, Mama,” Diane blurted out, “he did the pussy to me.”

Her mother didn’t believe her. “He told my mother that I was messing with him, and she believed him.”

As Bond grew up, her stepfather continued to prey on her. When she was a teenager, he would try to spy on her as she undressed. One night when she was thirteen, he came into her bedroom in his under shorts in the middle of the night. She looked up, saw him looking down at her, and screamed. Her mother put him out that night, but he soon came back.

In July, 1972, when Bond was 17 years old, she had argument with her mother. The family was living in Englewood at the time. It was about 10:30 or 11:00 at night. She can’t remember what the argument was about. “My mother was strict. It may have been because I came home late.” Upset, she ran out of the house. She was barefoot, wearing only shorts and a blouse. At 60th and Halsted, three men grabbed her. They took her to an abandoned building. One ripped her blouse off. Another kicked her between the legs. The third raped her repeatedly. They held her from 12:00 to 5:00 a.m. When they released her, she sat dazed and disoriented on a bench at 63rd and Halsted. A woman driver stopped and gave her a ride home. Her mother immediately called the police.

Bond remembers sitting on the sofa and talking with the police. They were, she said, “kind” toward her. She felt weirdly displaced. “It was as if I wasn’t there. Everything seemed very far away.”

The police apprehended the three men, and she brought charges against them.

That fall she returned to Crane High School. One day in September during lunch break she was outside the school. The boyfriend of her best friend Gail, known on the street as Son, told her that Gail, who had recently had a baby, wanted to see her. She was, he said, upstairs in an apartment in a nearby building. Diane noticed a group of teenage boys hanging out on the corner across the street.

“They’re not coming, are they?”

Son assured her they were not.

He led her upstairs into the apartment. The boys she had seen on the corner entered the apartment via the backdoor. There were five in all, including Son. She screamed. They held her down and took turns. The first to rape her was Son.

When they released her, she made her way back to school. She went to the principal and told him what had happened. He called the police. She was taken to Presbyterian St. Luke’s Hospital. The police brought one of the boys to the hospital, and she identified him. They then drove her around the area, and she identified the other four on the street. They were arrested and charged.

When the case came to trial, according to Bond, “the mothers lied for their sons” to provide them with alibis. The defendants were acquitted.

Bond’s mother told her that as she left the courtroom, she heard a man say, “If I was them, I wouldn’t have let her go. I’d have blown her brains out.”

The case arising out of the July rape was still in progress. Demoralized by the outcome of the September case, Bond didn’t go back to court. She dropped the case.

“Is it hard for you to talk about this?” I asked.

“I’m not crying on the outside,” she replied, “but I’m crying on the inside.”

Kicking the Pigeon # 3 - April 28, 2003

On the evening of April 28, 2003—two weeks after she filed a complaint with OPS about the April 13 incident—Diane Bond returned home at about 7:30 p.m. from the corner store. She encountered Officers Stegmiller, Savickas, Utreras, and Schoeff outside her apartment door. Also present was a fifth officer she later identified as Joseph Seinitz. He was tall and lean, in his thirties, with closely cropped blond hair. She recognized him as the officer known on the street as “Macintosh.”

The officers had two young men in custody. Demetrius Miller was one of them; she didn’t recognize the other. His name, she gathered, was Robert Travis. Bond recounted the incident to me the next day.

One of the officers barked at her, “Get the hell out of here!” Moments later, as she was descending the stairs, another yelled, “Come here!” Seinitz came down the stairs and grabbed her. Holding her by the collar of her jacket, he dragged her back up to the eighth floor, her body scraping against the stairs.

While Seinitz held Bond, Savickas punched her in the face and demanded, “Give me your fucking keys!”

“They snatched my jacket off and took the keys out of my pocket,” she told me. “I was so scared, I pissed on myself.”

The officers entered her apartment. They ordered her to sit on the sofa in her living room. The two young men, handcuffed, sat on her glass coffee table.

Stegmiller came in from outside the apartment and placed two bags of drugs on the top of her microwave. (He would later testify that he had found the drugs in an “EXIT” sign in the corridor outside her apartment.)

One officer stayed with Bond and the two boys, while the other three searched the apartment. The officer leaned back on her television cabinet where family pictures and religious artifacts were arrayed. She begged him not to sit on her icon of the Virgin Mary.

“Fuck the Virgin Mary,” he said, as he swept his hand across the top of the cabinet, knocking the Virgin Mary and other religious objects to the floor.

Seinitz and two other officer were searching Bond’s bedroom. They motioned to her to come into the room. They told her to pull down her pants. Then they told her to pull down her panties.

Seinitz brandished a pair of needle-nosed vise-grips and threatened to pull out her teeth if she didn’t cooperate.

“Why’d you pee on yourself?” one of them taunted.

They ordered her to bend over with her back to them, exposing herself. While she was in that position, they instructed her to reach inside her vagina "and pull out the drugs."

Bond was overcome by terror. As a child and young woman, she had, she told me, suffered repeated sexual abuse at the hands of men, including a gang rape when she was a high school student. Now, despite the official complaint she had made against these officers, they were again swarming around her, threatening her, cursing her, forcing her to undress. She feared they would rape or kill her. "I didn't know what they were going to do next." She only knew that each thing they did was worse than the last.

They brought her back into the living room. One of the officers instructed Travis to “stiffen up,” as he punched him repeatedly in the stomach.

“Do you want us to put a package on her?” the officer asked Travis.

“I don’t care what you do with her,” he replied.

They left with the two men.

Bond locked the door, collapsed on her sofa, and wept.

* * * *

A neighbor, Barbara White, who lives on the second floor of 3651 S. Federal, reported she too was assaulted that night by the same group of officers after they left Bond’s apartment.

White was employed at that time as a security guard. “I’ve lived here twenty-two years,” she told me, “and never had any problems.”

According to White, a friend named Bruce Reed came by at about 8:15 p.m. to see if she wanted anything from the store. When Reed came to the door, she was in the kitchen washing dishes. She said no. When he turned to leave, five police officers were at the door.

“What’s wrong?” White asked.

“You put my fuckin’ life in danger,” said one of the officers. White’s description of him—white, salt-and-pepper hair, about 40 years old—fits Stegmiller. She recognized him as one of the officers who some months earlier had demanded, in the course of searching her 16-year-old goddaughter, that the girl expose her breasts.

Stegmiller claimed White had yelled out the warning “Clean up!” when the police first arrived at the building earlier that evening. She denied she had done so. He slapped her across the face.

“You slap her,” he ordered Reed.

Reed refused. “I’m not gonna slap her.”

“If you don’t slap her, you’re going to jail.”

“You might as well take me to jail, ‘cause I’m not gonna put my hand on her.”

White tried to get to the telephone to call 911. Stegmiller blocked her path and threatened her, “Bitch, if you call 911, I’ll come back and fuck you up myself.”

The officers left. White called 911 and requested an ambulance which took her to Michael Reese Hospital. She was examined, then took the bus home.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, April 29, 2003, and continuing to the present; interviews with Demetrius Miller, Barbara White, and Bruce Reed; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officers Robert Stegmiller, Joseph Seinitz, Christ Savickas, Andrew Schoeff, and Edwin Utreras deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

Kicking the Pigeon # 2 - The Setting

Stateway Gardens, the community where Diane Bond has lived for the last twenty-seven years, is one of the high-rise public housing developments being redeveloped by the Chicago Housing Authority as part of its “Plan for Transformation.” Bounded by 35th and 39th Streets and State and Federal Streets, Stateway originally consisted of six seventeen-story and two ten-story high-rises on 33 acres. It provided 1,644 units of family housing. Under the redevelopment plan, private developers will build a “mixed income community” consisting of 1,315 units of housing, 439 of which will go to public housing residents. This “new community” will be called Park Boulevard.

The Stateway numbers—a net loss of 73% of the original public housing units—reflect the essential trajectory of the Plan for Transformation. City officials and developers speak of this massive reallocation of public resources to private hands in highly moralistic terms. Public housing developments, Mayor Daley has remarked more than once, lack “soul.” The new communities to be built on the land cleared by demolition will, so the logic goes, restore the soul of the city.

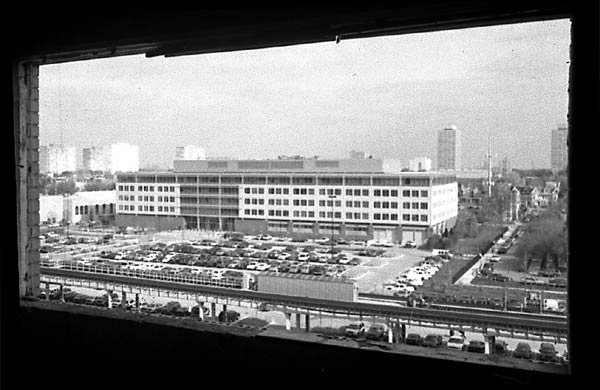

In a display that was part of an exhibition on the Plan for Transformation at the Chicago Historical Society last year—more an exercise in public relations for the CHA than historical inquiry—Stateway Gardens was described as "isolated." This characterization is consistent with the prevailing social scientific discourse on urban poverty. It is not, however, consistent with geography. It would be more accurate to say that Stateway, like most of the CHA archipelago, is not isolated but abandoned. Now that the rest of the Stateway buildings have been razed, Diane Bond looks out from her eighth-floor apartment, over the Bridgeport neighborhood and the Illinois Institute of Technology campus, at the downtown skyline. To the west, on the other side of the Dan Ryan Expressway, she can see White Sox Park. To the east, she can see De La Salle High School where both Mayor Daleys went to school.

And just out of sight, blocked from view by the eastern tier of her building, located three blocks away at 35th and Michigan, is the administrative headquarters of the Chicago Police Department. As I have observed elsewhere, the question posed by this landscape is: who has isolated themselves from whom?

* * * *

“It’s like a nightmare,” Bond told me the day after her encounter with the police. “All I did last night was cry.”

When I knocked on her door, she was cleaning up. She gave me a tour and showed me the damage—the shattered picture of the Last Supper, the damaged frame of Willie’s high school graduation picture, the broken drinking glasses, the clothes and objects strewn around Willie’s room, the one room she had not yet cleaned up.

I had at that time known Diane Bond for several years. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I worked out of an office on the ground floor of 3544 S. State, the building in which she lived. Every so often I would see her in passing, most often going to or coming from her job as a public school janitor. I didn’t know her well but formed an impression of a cheerful woman in coveralls who moved through the turbulent scene “up under the building”—at once drug marketplace and village square—with an easygoing, friendly manner.

In September of 2002, 3544 S. State was closed in preparation for demolition. Residents were given the choice of taking a housing voucher and moving into the private housing market or remaining on site. Bond opted to move to 3651 S. Federal. When the day came, the CHA provided moving vans for Bond and other residents relocating on site. At the end of the day, I encountered her, in a characteristically ebullient mood, ferrying the last of her possessions across the development in a shopping cart.

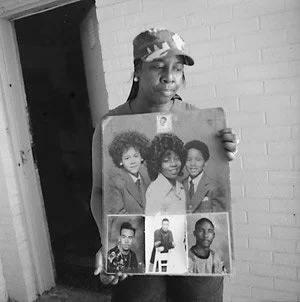

Her apartment in 3651 S. Federal is deeply inhabited. Two large, comfortable sofas, arrayed around a coffee table, dominate the living room. The top of the television cabinet functions as a sort of household altar for religious objects and family photos, among them pictures of her three sons: Delfonzo, now 30 years old, Larry, 29, and Willie, 21. Working as a janitor, Bond raised her boys as a single mother. She expresses pride in the fact that they have largely managed to stay clear of trouble in an environment where that is no small achievement. For the last three years, she has been involved with a man named Billie Johnson. Quiet and gentle in manner, Johnson labors in the economy of hustle—repairing cars, helping maintain the Stateway Park District field house and grounds, doing odd jobs for his neighbors.

* * * *

At my urging, Bond went to the Office of Professional Standards (OPS) of the Chicago Police Department to register a complaint against the officers who she said had assaulted her. As it happens, the OPS office is located at 35th and State in the IIT Research Institute Tower, the 19-story building visible from her apartment that stands like a wall of glass and steel between Stateway and the IIT campus to the north.

OPS investigates complaints of excessive force by the police. It is staffed by civilians and headed by a chief administrator who reports to the superintendent of police. When someone makes a complaint to OPS, an investigator takes down his or her statement of what happened. The individual is asked to review the statement and to sign it. In theory, OPS conducts its own investigation, interviewing the police officer(s) involved and any witnesses, then renders a judgment. In the vast majority of cases, it finds that the complaint is “not sustained”—i.e., the investigators could not determine the validity of the allegations of abuse. In a small number of cases each year, OPS sustains the complaint and recommends discipline for the officer(s) involved. An officer facing discipline may appeal to the Police Board, a body composed of nine civilians appointed by the mayor. The board has the power to reduce the punishment recommended by OPS or the superintendent and to reverse OPS altogether.

OPS has long been sharply criticized by human rights activists who argue that it functions not as a vehicle for holding the police accountable but as a shield against such accountability. They cite the numbers. For example, from 2001 through 2003, OPS received at least 7,610 complaints of police brutality. Significant discipline was imposed by the CPD in only 13 of those cases—six officers were terminated and seven were suspended for 30 days or more. In other words, an officer charged with brutality during 2001 – 2003 had less than a one-in-a-thousand chance of being fired.

It is, thus, extremely unlikely that an OPS investigation will yield any meaningful discipline for the officers involved. Yet it does not seem unreasonable to hope that a pending OPS investigation will at least serve to deter the officers named from further contact with the person who filed the complaint. That, at any rate, is what I told Diane Bond by way of reassurance.

Kicking the Pigeon # 1 - April 13, 2003

On Sunday, April 13, 2003, at about 5:00 p.m., Diane Bond, a 48 year-old mother of three, stepped out of her eighth floor apartment in 3651 South Federal, the last remaining high-rise at the Stateway Gardens public housing development, and encountered three white men. Although not in uniform, they were immediately recognizable by their postures, body language, and bulletproof vests as police officers. Bond gave me the following account of what happened next.

“Where do you live at?” one of the officers asked. He had a round face and closely cropped hair. Bond later identified him as Christ Savickas.

"Right there," she pointed to her door.

He put his gun to her right temple and snatched her keys from her hand.

Keeping his gun pressed to Bond's head, he opened her front door and forced her into her home. The other officers followed. As Bond stood looking on, they began throwing her belongings around. When she protested, one of them handcuffed her wrists behind her back and ordered her to sit on the floor in the hallway of the two-bedroom apartment.

An officer with salt-and-pepper hair, whom Bond later identified as Robert Stegmiller, entered the apartment with a middle-aged man in handcuffs and called out to his partners, “We’ve got another one.”

Bond’s 19 year-old son Willie Murphy and a friend, Demetrius Miller, were playing video games in his bedroom at the back of the apartment. Two officers entered the room with their guns drawn. They ordered the boys to lie face down on the floor, kicked them, handcuffed them, then stood them up and hit them a few times.

“Why are you’all doing this?” Bond protested.

Savickas came into the hall and yelled at her, “Shut up, cunt.” He slapped her across the face, then kicked her in the ribs.

In the course of searching the apartment, the officers threw Bond’s belongings on the floor, breaking her drinking glasses. Savickas knocked to the floor a large picture of a brown-skinned Jesus that sits atop a standing lamp in a corner of the living room.

“Would you pick up my Jesus picture?” Bond appealed to him.

“Fuck Jesus,” replied Christ Savickas, “and you too, you cunt bitch.”

Stegmiller then forced Bond to her feet, led her into her bedroom, and closed the door.

“Give us something to go on,” he told her. “If you don’t, we’ll put two bags on you.” He took off his bulletproof vest and laid it on the window sill. He removed the handcuffs from her wrists.

“Look into my eyes, and tell me where the drugs are. If you do,” he gestured toward the hallway where the man he had brought into the apartment was being held, “only that fat motherfucker will go to jail.”

Another officer entered the bedroom. Bond later identified him as Edwin Utreras. “Has she been searched?” he asked. “I’m not waiting on no female.”

Utreras took her into the bathroom and closed the door. He ordered her to unfasten her bra and shake it up and down. Sobbing, she did as he told her. He ordered her to take her shoes off. Then he told her to pull her pants down and stick her hand inside her panties. Standing inches away in the small bathroom, he made her repeatedly pull her panties away from her body, exposing herself, while he looked on.

“You’ve got three seconds to tell me where they hide it or you’re going to jail.” She extended her arms, wrists together, for him to handcuff her and take her to jail.

Utreras didn’t handcuff her. He returned her to the hall and ordered her to sit on the floor. An officer she later identified as Andrew Schoeff was beating the middle-aged man Stegmiller had earlier brought into the apartment. Bond and the boys looked on, as he repeatedly punched the man in the face.

“He was beating hard on him,” recalled Demetrius Miller. “Full force.”

Knocked off balance by his blows, the man fell on a framed picture of the Last Supper that was resting on the sofa. The glass shattered.

“There ain’t nothing in this house,” Bond kept insisting. “There ain’t nothing in this house.”

“Give us the shit, and we’ll put it on him,” said Stegmiller.

The name of the man to whom he referred, the man his colleague was beating, is Mike Fuller. On Fuller’s account, he had been descending from a friend’s apartment on the sixteenth floor, when he encountered Stegmiller coming up the stairs between the fifth and sixth floors.

“Where are you coming from?” Stegmiller demanded.

“From the sixteenth floor,” he replied.

“You’re lying,” said Stegmiller. “You’re coming from the eighth floor.”

He grabbed Fuller and searched him. Finding $100, Stegmiller pocketed it, then pushed him up the stairs. “I wouldn’t mind shooting me a motherfucker,” he said, “if you try to run.”

Stegmiller took Fuller to Bond’s apartment. “He kept telling me that’s where I’d run to,” said Fuller. Once inside the apartment, Stegmiller took a flashlight from a shelf in the kitchen and beat the handcuffed Fuller on the head with it. (“They don’t beat you,” he observed, “till after they cuff you.”) “If I find dope,” Stegmiller threatened, “it’s gonna be yours.”

“I saw how they ramshackled her house,” Fuller recalled.

The officers, having found no drugs, were now drifting out of the apartment. Stegmiller made a proposition to the two boys: if they beat up Fuller, they could go free. “If you don’t beat his ass,” he told Willie, “we’ll take you and your mother to jail.”

The boys put on a show for the officers. (“Hitting him on the arms, fake kicking,” Miller said later. “No head shots.”) After they threw a few punches, Stegmiller intervened and removed Fuller’s handcuffs “to make it a fair fight.” The three rolled around on the floor for a couple of minutes. The officers looked on and laughed.

“I told the boys to make it look good,” Fuller recalled. “It was for their amusement.”

Stegmiller applauded. He left laughing. No arrests were made.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, April 14, 2003, and continuing to the present; interviews with Willie Murphy, Demetrius Miller, and Michael Fuller; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al, a federal civil rights suit brought by Ms. Bond.

Officers Robert Stegmiller, Christ Savickas, Andrew Schoeff, and Edwin Utreras deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the date alleged.

Restoring The View

Today The View From The Ground resumes publication. It has been two years since we last posted a story. The reasons for this hiatus are personal. We certainly had not completed our mission. Nor had we exhausted the possibilities of The View. We were just beginning to grasp the nature of the tools that we, in collaboration with our readers, were developing.

We resume publication today in a radically altered landscape. Several years ago, I joked in print that the name of Chicago’s public housing strategy—“The Plan For Transformation”—was Orwellian: the Chicago Housing Authority, which had failed to provide “maintenance” and “security,” was now promising “transformation.” (Only as the process gathered momentum, did I realize that the truly Orwellian word was “plan.”) Yet the name has, in fact, proved accurate.

When we posted our first story in the spring of 2001, the Stateway Gardens public housing community, the ground from which we viewed the city, was largely intact. Today the “State Street corridor,” dominated by the Robert Taylor Homes and Stateway Gardens, has indeed been transformed. No other word will do. Once the largest concentration of public housing in the nation, it is now a post-apocalyptic landscape, block after block of vacant land. Of the twenty-eight high-rises that comprised Robert Taylor, two remain standing; of the eight Stateway buildings, one remains. At these and other former public housing sites throughout the city, developers have erected billboards proclaiming the names of the new “mixed income communities” they are building on the land cleared by demolition. Stateway Gardens, for example, has been renamed “Park Boulevard.”

Until recently, a billboard promoting Park Boulevard stood at the corner of 35th and State, the northern boundary of Stateway. The sign was a montage of photographic images: a boy blowing on a dried dandelion, a grandfather with his arm draped around his grandson, a little girl held aloft by strong, loving arms. Lightly superimposed upon these images were a series of words: “family, dreams, life, diversity, laughter, happiness, hope, fun, together, learning, independence, sharing, success.” Four words were in a darker font than the rest. They occupied the foreground and formed the phrase:

A Community Coming Soon

This message was meant to be read with reference to the acres of vacant land to the south of the billboard. It was intended to promote the idea that the developers would create on this blank slate a new community embracing the qualities evoked by the words on the sign. The inescapable, if perhaps unintended, subtext of this message was that those words did not apply to the generations of Stateway residents for whom this place had been home. The redevelopment process is necessarily blind to the forms of community they have created. It is a process of erasure rather than renewal.

For two years, The View reported from the Stateway community, as it contended with the forces pushing it toward invisibility. The words “the view from the ground” suggest both a moral stance and a methodology. Our understanding of what they mean has deepened over time. In our initial statement of purpose, we wrote:

The tradition of reporting from which The View takes its bearings seeks to create the means for those who are voiceless and caricatured within the prevailing discourse to be heard and seen on their own terms.

This is not to claim, as some have said, that The View “gives voice to the voiceless.” Those in abandoned communities such as Stateway, who are barred from full participation in the society by conditions of structural exclusion, do not lack voices. They lack the means of self-representation. Using the crafts and media at our command, we have tried to make immediate the voices of those who have told us their stories.

We have done so as friends, as neighbors, and, in some instances, as actors in those stories. For a number of years, we have been deeply engaged in the life of the Stateway community. How does our solidarity with those we report on affect our reliability as reporters? Does it distort our vision? Or does it perhaps afford us access to perception? These are legitimate questions. We leave them to our readers to assess. We make no claims to journalistic “objectivity.” We do aspire to intellectual rigor. As the British journalist James Cameron observed in his memoir Point of Departure:

I still do not see how a reporter attempting to define a situation involving some sort of ethical conflict can do it with sufficient demonstrable neutrality to fulfill some arbitrary category of “objectivity” . . . . I may not always have been satisfactorily balanced; I always tended to argue that objectivity was of less importance than the truth, and that the reporter whose technique was informed by no opinion lacked a very serious dimension.

We have understood our work within the traditions of human rights reporting. This form of inquiry begins with the injury to human dignity in the individual case. Having established the reality and unacceptability of the abuse, it moves to interrogate larger systems. Is this instance part of a larger pattern? What is the extent of that pattern? What conditions contribute to the space in which such abuses occur?

This orientation is, for us, an essential aspect of the meaning of “the view from the ground.” We have sought to engage fundamental human rights issues by immersing ourselves in eight square blocks of the South Side–by staying close to the ground.

Today most of that ground, cleared and fenced, awaits redevelopment. Life persists amid the ruins. Some seventy-odd families inhabit the one remaining building, 3651-53 South Federal. Community members who have relocated elsewhere return to see friends, to hang out, to walk familiar streets. The Park District field house–known as “the center”–remains full of activity. Yet it would be false and sentimental to understate the extent of the damage.

The machinery for disappearing people and erasing places is stunningly effective. We published The View from an office in a first floor apartment in one of the Stateway high-rises, 3542-44 South State. I knew everyone in the building; everyone knew me. I wrote a good deal about that building and know many more stories than I have written. After the building was closed, I came back almost every day over a period of months, sometimes for hours at a time, to bear witness to the process of demolition. Yet if I stand today on the vacant lot where 3542-44 South State was located, it takes a large, sustained effort of imagination to remember what was there.

Whatever else might be said about Chicago’s vertical ghetto, you could see it. As you moved through the city, it was difficult not to see public housing high-rises. Even registered in passing at the periphery of your vision as you drove by at 60 mph on the expressway, they posed questions, unsettled the mind, and abraded the conscience. The invisible ghetto fast replacing the high-rises allows us to move through the city unimpeded by moral friction and relieved of the danger of colliding with fundamental issues of social justice.

This restructuring of the city, it is important to recognize, is also remapping the geography of our moral imaginations—what we can see and what we can think, how issues are constructed and the parameters within which they are discussed.

It has been said that the more effective a regime of censorship is, the less people are aware of it. Some struggles over freedom of speech

have taken the form of demanding that censorship be kept visible, e.g., that material suppressed from publications be shown by white space (in India during the State of Emergency) or by ellipses (in Poland under martial law). (The latter practice gave rise to an inspired Solidarity button that read simply: “. . . “) Something similar can be said of structures of exclusion: the more invisible they are, the more effective. The less we are aware of them, the more powerfully they shape our experience of the world. They are part of the given; we are inside the whale. This is, arguably, the ultimate paradox of the Plan For Transformation: as the City has torn down the high-rises, it has fortified the structures of exclusion.

Paul Farmer has observed:

Human rights violations are not accidents; they are not random in distribution or effects. Rights violations are, rather, symptoms of deeper pathologies of power and are linked intimately to the social conditions that so often determine who will suffer abuse and who will be shielded from harm. If assaults on dignity are anything but random in distribution or course, whose interests are served by the suggestion that they are haphazard?

Narrative inquiries into the conditions underlying patterns of abuse must move against a powerful undertow. The boundaries of permissible discourse, the conventions of “on the one hand. . . on the other hand” journalism, and, in some instances, the very structure of the built environment resist such narratives. The costs of perception are high. It is easier to see assaults on human dignity as malfunctions of otherwise sound policies and institutions (the work perhaps of “a few bad apples”) than as “symptoms of deeper pathologies of power.”

We have no illusions about how difficult it is to tell such stories. It is not simply a matter of providing reliable information. Good journalistic work can readily be assimilated to the prevailing structures of perception. It is necessary to subvert those structures—to break through—in order to create space for fresh perception. This is the work of art and nonviolent resistance, as well as human rights reporting. The View is a point of intersection between these traditions, sensibilities, and conversations.

The View will continue to report from the ground. We will report from the places to which people have been disappeared. And we will describe the machinery by which individuals, populations, and issues are rendered invisible. Above all, we will work to develop narrative, analytic, and graphic strategies to illuminate the pathologies of power.

We don’t know where our inquiries will take us. We have a strong sense of direction but no map. We invite readers to join our ongoing conversation about how best to tell particular stories. What are the requirements of the narrative? the most effective lines of inquiry? the best means of making the invisible visible?

This much is clear. Conditions of structural exclusion are ultimately enforced by violence: by particular blows inflicted by particular hands on particular bodies. That is our point of departure—the ground from which we take our bearings—as we now resume The View.

About

The View From the Ground is an occasional publication of the Invisible Institute—a set of relationships and ongoing conversations grounded at the Stateway Gardens public housing development on Chicago’s South Side. In the tradition of human rights monitoring, our aim is to deepen public discourse by providing reliable information about conditions on the ground. The View orients from the perspective of those living in abandoned communities. There are, we recognize, other perspectives on the changes transforming inner city neighborhoods. We are mindful of these perspectives. Our first responsibility, however, is to evoke the experience of those on the ground—those for whom these neighborhoods are home. Public discourse is deformed by the absence of this perspective. The View seeks to inject it into the public conversation. Investigative journalism and human rights reporting are often challenged on the ground that they do not afford the powerful an adequate opportunity to tell their side of the story. Such criticism is based on a misconception about the nature of such reporting. Powerful institutions and individuals do not lack vehicles for expressing their views and asserting their interests. The tradition of reporting from which The View takes its bearings seeks to create the means for those who are voiceless and caricatured within the prevailing discourse to be heard and seen on their own terms. Such reporting does not purport to be “balanced” in the sense that the reporting in the mainstream press does. (Indeed, one of its aims is to correct distortions that arise from the conventions of “objective” journalism.) That does not, however, mean that it claims an exemption from high standards of craftsmanship and rigor. On the contrary, the moral authority of a human rights monitoring effort rests ultimately on the quality of its reporting. That is the basis on which we expect The View to be judged.

Help Us

The View From The Ground is dedicated to enriching the public conversation about a range of issues associated with abandoned communities. We need your help to broaden and deepen that conversation. If you find The View useful, if you think it provides information and access to perception not available elsewhere, we ask that you help us extend its reach. Who do you know who might benefit from The View? Please recommend it to them and urge them to subscribe. Do you know of networks through which The View might be made available? If so, please let us know. The View is a tool for holding public institutions accountable to the marginalized and disenfranchised. Its impact has exceeded our expectations.That impact would be further enhanced, if public officials and other decision-makers knew it was being read and discussed by an expanding number of engaged citizens. Thanks for your help in spreading the word.

The State Street Coverage Initiative Part Four (Copy)

The View posted Part II of this story on the morning of March 21. That afternoon, for the first time since January 7, there was no visible police presence on the 3700 block of South State Street. We later learned that 2nd District personnel had been deployed downtown because of anti-war protests. It is thus hard to judge the impact, if any, of the View report. In any case, there have been no police cars stationed at fixed locations on South State Street since March 21.

The State Street Coverage Initiative has, it appears, been suspended for the time being, but the questions it raised remain open.

Harriet McCullough of Citizens Alert, a police accountability organization, posed some of those questions in a February 24 letter addressed to Superintendent Hillard and copied to Mayor Daley and Demetrius Carney, president of the Police Board, a civilian disciplinary board appointed by the mayor. After recounting complaints her organization had received about the Initiative—including one from Kate Walz, a Citizens Alert board member threatened with arrest for standing on State Street—Ms. McCullough asked:

Why was this police policy undertaken?

Why are the residents of South State Street and other people not being allowed to meet or talk on the 3500 to 3700 blocks of South State?

How do you justify this allocation of police manpower, in light of pressing needs in this community and elsewhere in the City?

Ms. McCullough received a reply, dated March 7, from Mr. Carney. “The Police Board does not control police personnel assignments or patrol practices,” he wrote. “The questions you raise fall directly under the responsibility of the Superintendent of Police.”

At the Police Board hearing on March 13, Ms. McCullough asked Superintendent Hillard directly, “Why was such a police policy undertaken?”

The Superintendent flatly denied that the State Street Coverage Initiative was a matter of policy.

“I can tell you truthfully,” he said, “that there is not a written police policy to that effect. We’ve had a number of complaints of drugs being sold and gang members recruiting and trying to sell drugs up and down the State Street corridor. We’re still in an enforcement phase of that, but when it comes down to stopping anybody and everybody along the State Street corridor, that shouldn’t be happening, and I don’t think it’s happening.”

“We are just concerned,” Ms. McCullough replied, “that people aren’t being allowed to meet or talk on State Street.”

“Other people,” said the Superintendent, “are concerned that people might come into their respective neighborhoods from outside the neighborhood and outside the city and purchase drugs and things like that.”

I made a brief statement to the Board in which I described what I had observed on State Street—citizens arrested for being on the street, told they could not await at the bus stop, given jaywalking tickets, and so on. What, I asked, was the rationale for the massive allocation of police manpower to one-and-a-half blocks of State Street?

Superintendent Hillard again stated that the State Street Coverage Initiative “is not a policy of the Chicago Police Department.” He went on to say, “People should be able to patronize the library. People should be able to stand on the street and catch the CTA bus, if they need transportation. People should be able to go to the stores.” Again, he emphasized “drug dealers and gangbangers along the State Street corridor” as the rationale for the increased police presence.

Following the Police Board hearing, Ms. McCullough received a response to her letter to Superintendent Hillard. Dated March 12, it was signed by Commander Marienne Perry of the 2nd District.

Commander Perry writes:

In response to your letter of February 2003, there has been a visible Chicago Police Officer presence in the area of 37th and State Streets for several weeks. The officers are there in response to citizens’ complaints of being intimidated by large groups gathering at the location.

Her phrasing suggests that the State Street operation began in mid-February. In fact, it began, with great intensity, on January 7 and was sustained without lapse until mid-March.

She continues:

The complaints allege that people cannot enter restaurants nor can they use the library without fear of being harmed. Library workers and patrons are in fear because those who gather on the street come into the library to use narcotics in the restrooms and engage in other unlawful acts which are allowed to occur because citizens are afraid of reprisals.

She then states a rationale for the State Street Coverage Initiative:

The police presence is there to ensure that law-abiding citizens can safely walk the streets and make use of the resources of this Community without fear. Officers are not there to infringe upon the personal freedoms of anyone but they are there to make sure that innocent residents are not forced to live in a perpetual state of fear.

The responses of Superintendent Hillard and Commander Perry to questions raised about the State Street Coverage Initiative are striking in several respects:

By forwarding Ms. McCullough’s letter to Commander Perry for response, the Superintendent, in effect, redefines the State Street Coverage Initiative as a local response to local complaints. But on the evidence of Chief of Patrol Maurer’s January 9 order, the directive to clear State Street came from the highest level of the CPD and was addressed to multiple divisions within the Department. (Commander Perry was one of ten commanders and deputy chiefs of patrol to whom the order was addressed.)

Superintendent Hillard repeatedly stated that the State Street Coverage Initiative was not a police policy. This statement would seem to be contradicted not only by police practices sustained over a period of two-and-a-half months but by internal CPD documents—the Chief of Patrol’s January 9 order and Commander Perry’s memo to personnel under her command. In order to resolve this apparent contradiction, The View has submitted a request to the CPD under the Freedom of Information Act for any other documents pertaining to the State Street operation—above all, the initial order to which the Chief of Patrol’s January 9 order on reporting procedures is an addendum.

Commander Perry’s letter states that the heightened police presence on South State Street was in response to citizens’ complaints. There is no question that the librarians at the Chicago Bee Branch Public Library, merchants on State Street, and Stateway Gardens management have made occasional complaints to the police. It is equally clear that the State Street Coverage Initiative was not undertaken in response to their complaints. The evidence strongly suggests that it was prompted by the complaint of one particular citizen: Mayor Daley.

Superintendent Hillard cited “drug dealers and gangbangers along the State Street corridor” as the rationale for the heightened police presence, but in practice what distinguishes the State Street Coverage Initiative from customary patterns of policing in public housing is precisely that it was directed not at drug dealers and gang members engaged in criminal activity but at citizens engaged in non-criminal activities—walking, talking, standing—on the public street. The defining image of the Initiative, repeated countless times, is of police officers ordering citizens off the street or giving jaywalking tickets within sight of open drug dealing.

Commander Perry does not explicitly mention drug dealing and gang activity as rationales, but note the language she uses: “intimidate . . . fear of being harmed . . . in fear . . . afraid of reprisals.” Are we to understand that what the Commander describes as “a perpetual state of fear” is created by jaywalking? Certain patterns—blocking the entrance to the library, selling loose cigarettes, crossing the street outside the white lines—can be seen as problems without evoking a community held hostage by fear.

The rhetorical strategies adopted by Superintendent Hillard and Commander Perry in response to questions raised about the State Street Coverage Initiative make it necessary for them to portray the community in highly negative terms: it is dominated by drug dealers and gangs, community members live in “a perpetual state of fear,” and so on. Their efforts to justify a questionable police policy thus contribute to public perceptions of the community as a dangerous haven for crime. This criminalization of the community in turn facilitates the City’s program of land clearance—it lends support to the conclusion that the community is not viable and so should be obliterated rather than renewed. In this connection, it is important to recall that the State Street operation appears to have originated not in the CPD but in the Mayor’s office and to have been motivated not by concern for the safety of neighborhood residents but by the City’s development agenda.

Commander Perry evokes the fears of citizens as a rationale for the State Street Coverage Initiative. Public safety is indeed a central aspiration of Stateway residents. As their community undergoes “transformation”—forced relocation, demolition, redevelopment—they have again and again called for respectful, sustained law enforcement. At the moment, however, on the evidence of scores of conversations with community members in recent weeks, it remains a place where—to use Commander Perry’s terms—conditions of intimidation, fear of being harmed and fear of reprisals arise primarily from the way the police conduct themselves in public housing.

In her letter to Ms. McCullough, Commander Perry states: “The police presence is there to ensure that law-abiding citizens can safely walk the streets and make use of the resources of the Community without fear. Officers are not there to infringe upon the personal freedoms of anyone. . .” This is a welcome principle. The question is how best to implement it. Whatever else might be said about the State Street Coverage Initiative, it has been an extravagantly wasteful strategy for accomplishing these ends—wasteful of police resources and wasteful of citizens’ constitutional rights.

A Note to Readers

I apologize for the lapse in publication. For several months, The View has been experiencing at first hand the rigors of forced relocation. Our office was located in 3544 South State Street, one of the Stateway Gardens high-rises demolished over the last few months. It was our understanding that the CHA would prepare space in one of the remaining Stateway buildings for the programs housed in the office. After delays and confusion, it was communicated by various means that none of these programs would be given alternative space at Stateway, if I was in the office.

We conceived of our office in 3544 South State—a five-bedroom apartment on the first floor—as a small settlement house: a common home for neighboring programs and initiatives that support and enrich the lives of Stateway residents. Acting on behalf of the Stateway Local Advisory Council (LAC)—the resident council—my colleagues and I established working relationships with an array of institutions and invited them to work out of the office. Among them: the CARA Program (a job training organization working with at non-leaseholders); the Mandel Legal Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School (with which we collaborate on a police accountability project); the Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago (providing legal services); the Family Institute of Northwestern University (providing mental health services); and Archeworks, a non-profit design studio. Traditions of resident employment in the office evolved into an independent organization, 32 Degrees, that facilitates public health programs and trains residents as outreach workers. The office also served as a base for reporters (from Chicago, national, and neighborhood media), documentary-makers (from NPR, PBS, CBS’s “60 Minutes II”), and researchers exploring public housing issues. It was in this rich, nourishing ecology that The View was born and developed.

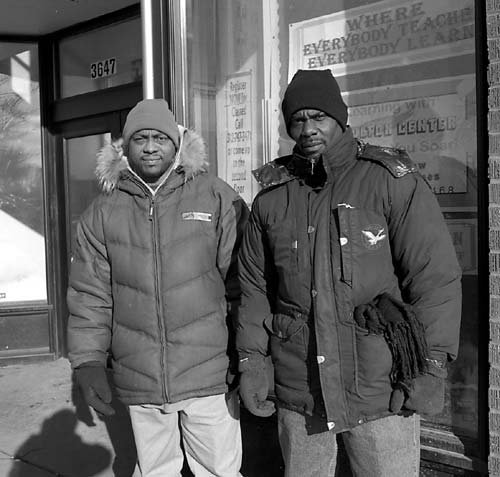

When it became apparent that programs serving Stateway residents were, in effect, being held hostage by the CHA’s refusal to provide me with space, I withdrew from the office I had helped create. In the intervening months, I have worked out of my pick-up truck, the Chicago Bee Branch public library at 3647 South State, and the LAC office at 3653 South Federal. The LAC has generously invited me to reestablish The View at its office, and I am in the process of doing so.

I mention this matter now for two reasons:

First, the question of how the CHA responds to public criticism—and to its critics—is central to the piece that follows on the independent monitor of the relocation process. Large public and private institutions can always invoke seemingly neutral reasons (e.g., budgetary constraints, shifting funding priorities, obscure regulations and contract provisions that suddenly cry out to be enforced, etc.) to justify attempts to silence their critics—or more precisely, to induce them to censor themselves. This tendency is perhaps best thought of as an institutional reflex rather than as a conscious policy: in the absence of an explicit commitment to open public discourse, official responses to criticism will be skewed in that direction.

Second, I want to reassure readers that The View is back. I have stepped away from relationships I value, in order not to put the work of friends and colleagues at risk. This has involved a measure of loss for me. It has also renewed my sense of freedom. In coming months, we will work to increase the capacity of The View and to extend its reach. Among the stories we are preparing is a series on the policing of public housing and a journal of a demolition—an account of the process by which 3542-44 South State became a vacant lot.

It’s good to be back in action.

Report #5 of the Independent Monitor

My first three reports dealt with the ongoing relocation process in Phase II (2002). My fourth report addressed the timing of future phases of the process. This report deals with my recommendations as to how various aspects of the process might be improved in future years.

Report #4 of the Independent Monitor

Our agreement provides that I will consult with representatives of the CHA and the CAC to convey any interim recommendations I may have for improvements in the Phase II relocation process. Report No. 1 was submitted to you on July 24, Report No. 2 on August 5, and Report No. 3 on September 11. I now submit Report No. 4.

Report #3 of the Independent Monitor

Our agreement provides that I will consult with representatives of CHA and CAC to convey any interim recommendations I may have for improvements in the Phase II Relocation process. Report No. 1 was submitted to you on July 24, and Report No. 2 was submitted to you on August 5. I now submit Report No. 3

Report #2 of the Independent Monitor

Our agreement provides that I will consult with representatives of CHA and CAC to convey any interim recommendations I may have for improvements in the Phase II Relocation process. Report No. 1 was submitted to you on July 24. I now submit Report No. 2

Report #1 of the Independent Monitor

Our agreement provides that I will consult with representatives of CHA and CAC to convey any interim recommendations I may have for improvements to the relocation process. Accordingly, I submit the following